Inga Ulnicane

EU research policy has experienced tremendous growth in terms of increase in the EU-level competences, funds, initiatives and policy instruments. While today EU research policy is taken for granted, in the early days of European political integration in the 1950s its establishment was far from obvious. Initial treaties did not envisage European level competencies or funds in this area. Major breakthroughs took place during the 1980s when the EU-level competence was established and the Framework Programme was launched to fund research. The growth of EU Framework Programmes (FPs) for research from approximately 3 billion Euros allocated for the 1st FP (1984-1987) to almost 100 billion Euros earmarked for the current Horizon Europe (9th FP, 2021-2027) is just one example that demonstrates considerable expansion of EU activities in this area.

EU research policy has experienced tremendous growth in terms of increase in the EU-level competences, funds, initiatives and policy instruments. While today EU research policy is taken for granted, in the early days of European political integration in the 1950s its establishment was far from obvious. Initial treaties did not envisage European level competencies or funds in this area. Major breakthroughs took place during the 1980s when the EU-level competence was established and the Framework Programme was launched to fund research. The growth of EU Framework Programmes (FPs) for research from approximately 3 billion Euros allocated for the 1st FP (1984-1987) to almost 100 billion Euros earmarked for the current Horizon Europe (9th FP, 2021-2027) is just one example that demonstrates considerable expansion of EU activities in this area.

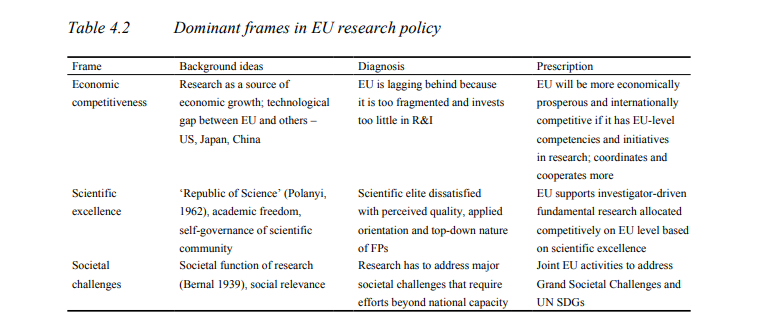

How to explain the emergence and expansion of EU research policy and funding? In my recent publication ‘Politics of public research funding: the case of the European Union’ (Ulnicane 2023), I use framing approach to highlight that the establishment and expansion of EU research policy and funding are not just a technocratic issues but have important political and social aspects which are deeply intertwined with the history and political agenda of EU integration. To examine political dynamics of EU research policy and funding, I study the role of three dominant frames: economic competitiveness, scientific excellence and societal challenges (see the Table). Similar frames can be encountered in national science, technology and innovation policy, for example, in recent Artificial Intelligence policy. However, a specific feature of EU research policy is that these frames explain problems and propose solutions referring to the EU level cooperation and competition.

Economic competitiveness

Economic competitiveness has been a dominant frame driving the establishment and growth of the EU research policy for over some 60 years (Ulnicane 2022). Initially, European integration mostly focused on economic cooperation. In this context, research was mainly valued in economic terms as a contributor to economic growth and prosperity. An important element of this frame was a concern that Europe was lagging behind the US in its research and development. As Veera Mitzner shows in her brilliant book ‘European Union Research Policy. Contested Origins’ (Mitzner 2020), ‘technology gap’ rhetoric was a major driving force behind the early discussions about EU level research policy that called for European cooperation in research because no individual European country can compete with the US on its own.

Over the years, in addition to initial concerns about the technology gap with the US, new worries have emerged about the EU lagging behind Japan and more recently China. These concerns have provided important rationales for the Lisbon strategy and European Research Area launched in 2000 (Ulnicane 2015) as well as for investing in research after the 2008 financial crisis (Ulnicane 2016). Despite the criticism of the economic competitiveness rhetoric highlighting that countries do not compete like companies and international technology development is not a zero sum game, it remains widely used. While in the past 20 years two additional major frames – scientific excellence and societal challenges – have emerged in EU research policy, economic competitiveness frame is still very popular and influential in discussing investments in EU research.

Scientific excellence

Scientific excellence frame is very much about supporting scientific freedom and ‘blue sky’ fundamental research. For a long time, the support for basic research in the EU was mainly left to national research funders. However, several developments contributed to the introduction of scientific excellence frame in EU research policy in the early 21stcentury. First, scientific elite was dissatisfied with the FPs due to the perceived quality issues, top-down character and applied nature. Second, the so-called European paradox rhetoric was challenged. If traditionally it was assumed that the EU is good in fundamental science but weak in application, then increasingly it was demonstrated that the EU is also lagging behind in basic science.

To address these problems, it was suggested to extend the idea of ‘European value added’ beyond European cooperation and coordination to include Europe-wide competition as well. These ideas led to the establishment of the European Research Council that provides highly competitive grants for investigator-led frontier research.

Societal challenges

At the time when the idea of scientific excellence became popular in the EU, a very different concept of societal challenges was promoted around the world by private foundations, international organizations, national governments and research organisations. Societal challenges frame, also known as Grand Challenges or global challenges frame, emphasizes that research should address most urgent societal issues of our times in areas such as health, environment and energy.

In the case of the EU, cross-border character is seen of particular importance, calling for European cooperation on these challenges. In the current Horizon Europe programme, the focus of global challenges pillar is on five missions, such as cancer, adaptation to climate change and healthy oceans. It is envisaged that these missions will contribute to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. However, initial experience has revealed that implementation of missions is challenging and interest in relevant calls has been low.

Other frames: Cohesion & defence

In addition to the dominant frames discussed above, we can also find some other frames in EU research policy. One such frame focusses on cohesion within the EU. There are huge differences in research performance across the 27 member states. Performance is lagging in eastern and southern member states, which receive dedicated support from EU structural funds and other sources to build their research capacities and reform their research systems. Another more recent frame focuses on defence research. While typically defence research has been perceived as highly sensitive area of national sovereignty, the launch of the European Defence Fund comes with the funds for collaborative defence research to jointly address new security threats and challenges.

Is EU research policy a success story?

The continuous growth of EU research policy and funding has been deeply intertwined with the political agenda of EU integration, providing a good illustration to the claim that research investments are ‘a continuation of politics by other means’ (Elzinga 2012: 416). The Framework Programme constitutes the third largest spending item on the EU budget after agriculture and regional funds (Ulnicane 2016). Moreover, research is also funded from other EU funding programmes for regional funds and defence. But is the growth of funding and policy area enough to claim that EU research policy is a success story? Success story of what and for whom? Who has benefited from this growth? What have been the impacts and results for EU citizens and taxpayers?

If you would like to learn more, watch this seminar on EU research policy, Framework Programmes and European Research Area.

Dr. Inga Ulnicane is Senior Research Fellow at De Montfort University, UK. She has published widely on topics such as EU research policy, governance of emerging technologies, politics and policy of Artificial Intelligence and Responsible Research and Innovation. In addition to academic publications, she has also prepared policy reports for the European Parliament and European Commission.

References:

Elzinga, A. (2012) Features of the current science policy regime: Viewed in historical perspective. Science and Public Policy 39(4): 416-428. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs046

Mitzner, V. (2020) European Union Research Policy: Contested Origins. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41395-8

Ulnicane, I. (2015) Broadening aims and building support in science, technology and innovation policy: The case of the European Research Area. Journal of Contemporary European Research 11(1): 31-49.

Ulnicane, I. (2016) Research and Innovation as Sources of Renewed Growth? EU Policy Responses to the Crisis. Journal of European Integration 38(3): 327-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1140155

Ulnicane, I. (2022) ‘Introduction – technologies and European Integrations’, in T. Hoerber, I. Cabras and G. Weber (Eds) Routledge Handbook of European Integrations, Routledge, pp.199-207.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429262081-15

Ulnicane, I. (2023) Politics of Public Research Funding: the case of the European Union. In: Lepori B., Jongbloed B., and Hicks D. (Eds) Handbook of Public Funding of Research, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp.55-71.https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800883086.00009

This blog post was initially published on Europe of Knowledge blog.